Client Spotlight: Tapper Legacy

We’re delighted to announce the launch of Tapper Legacy!

Tapper is an incredible opportunity to share your stories with your family, friends, and loved ones. You will never have to leave anything unsaid or any story untold. It’s an app where your legacy can live on for generations to come.

We built this app for Tapper Technology from the ground up as a foundational product – meaning they will be able to reliably build upon it into the future. With a tech stack including Rails, Swift on iOS, and Kotlin for Android, we were able to quickly and cheaply build an MVP that will allow them to hire from a large pool talented developers internally when the time comes, quickly iterate on new features, and not sacrifice on quality.

Download the Tapper Legacy app today and start safeguarding your legacy!

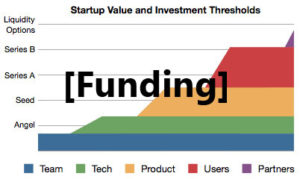

There is a standard path that startups go down when looking to raise institutional capital.

There is a standard path that startups go down when looking to raise institutional capital.